UNITED STATES PARKOUR ASSOCIATION

On Equal Prize Money and Women’s Participation in Parkour Competitions

2022 AUGUST 13

Adrienne Toumayan

Introduction

When Sport Parkour League (SPL) announced on July 12 that they would be offering equal prize money to all athletes at this year’s event, I was delighted and relieved. I was also confused. Only two months earlier, I had been talking with SPL Co-Founder Tom Coppola about the topic of equal pay and he had outlined all the reasons why they would continue not providing an equal purse for men and women. What changed his mind? I also felt exhausted, agreeing with a disheartened message I received from APEX Founder/Owner Ryan Ford reflecting on the fact that APEX made the decision back in 2016 to offer equal prize money to men and women, but somehow it is still a controversial question six years later. Controversial, indeed. While some companies have made commendable strides toward gender equality and inclusion, others continue to rationalize exclusionary practices or take a passive approach by telling women the door is open, they just need to work hard enough or want it badly enough. Others sit in the middle — slowly working toward a more inclusive future for our sport, but perhaps not fast enough. This article aims to peel back the curtain just a little on some of these organizations, looking at how and why they make the decisions they make — or made — around women’s participation in parkour competitions. I spoke with the organizers of events past and present, including the Air Wipp Challenge, APEX International, Pr/etty Parkour’s Pretty Flow Competition, SPL’s North American Parkour Championships (NAPC), Tempest Freerunning’s TMPST Onlines and Kings of the Concrete (KOTC) event, and Red Bull Art of Motion (AOM).Background and Timeline

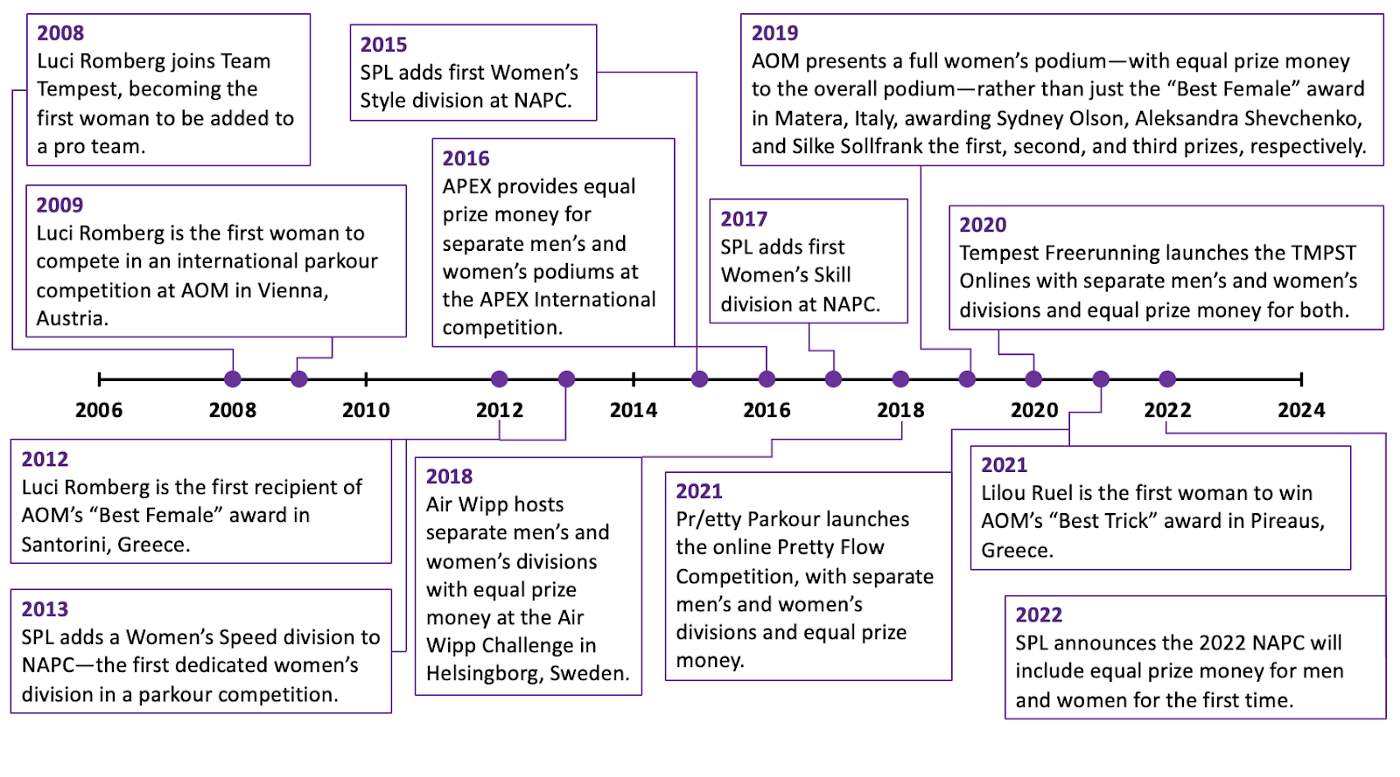

Before we get started, I want to highlight a few key moments in women’s parkour competition history that are relevant to the discussion below; not an exhaustive list, by any means, but moments that struck me during my research for this article.(Some) Key Moments in Women’s Parkour Competition History:

As seen in the timeline above, women have been competing in parkour competitions for over a decade. Yet, there is still no industry standard for how we include women in competitions — separate vs. mixed divisions — and whether women earn the same prize amount as men. This lack of standardization makes sense when you look at the parkour industry as a whole. While we do have an international governing body in Parkour Earth, the organization is still relatively young and they’ve yet to take on the topic of competition in terms of setting international standards. Even at the country level, only a small number of governing bodies exist around the world and fewer still prioritize or are well-established enough to host or support national competitions. As a result, competition standards have been left to the event organizers themselves.

On a positive note, this allows us the flexibility to experiment with the best competition formats to meet our needs and celebrate the creativity and freedom that we value above all else. And experiment, we have. We’ve seen it all, from an expertly curated Speed, Skill, and Style format in a gym setting, to freerunning across boats or rooftops while broadcasting via TikTok, to a closed-door event with breakdance-style brackets — and everything in between. Unfortunately, this also means experimenting with how and when to include women, including trans women, in these events — a result of being a male-dominated discipline with very few women in decision-making seats or positions of power.

Women and Parkour Competitions: A Closer Look

Art of Motion and Sport Parkour League

When AOM was first held in 2007, the concept of a parkour competition was extremely new and raised a lot of eyebrows. Despite this, a portion of our community saw competition as an important path to explore and pursue, and it didn’t take long for women to want in too. Luci Romberg — arguably the most famous female freerunner — asked to compete at AOM in 2009, and was immediately thrown in to hold her own in the boys’ club. AOM Sport Director Nico Martell said he was excited for her to compete alongside the men, deciding back then that AOM would remain a mixed event. He noted that with separate divisions, we would lose the opportunity to witness key moments like Luci placing above Pavel ‘Pasha’ Petkuns at one event or French powerhouse Lilou Ruel out-scoring Farang team member and Red Bull sponsored athlete Dominic ‘Dom Tomato’ Di Tommaso in the spot challenge at the 2022 event. Nico envisions a future where men and women are competing against each other for the same podium spots on equal footing. Until then? AOM will continue to hold a mixed competition, with men and women completing their runs alongside each other in the same heats but fighting for spots at separate podiums — the overall podium and the women’s podium. That is, until a woman places high enough to win both the overall and the women’s prize. And then what?

Podium duplicity aside, AOM does provide equal prize money for the overall and women’s podiums — Nico emphatically stated that equal prize money should always be the standard without question. A welcome statement from one of the most popular freerunning competitions! However, there are far fewer spots available for women to compete. Red Bull, and Nico himself, came under fire this year after the 2022 AOM event was announced and the community noticed that of the 16 total participants, only three were women. The Red Bull website outlines that, “Those 16 lucky freerunners [competing in 2022] include the top-three men from Red Bull Art of Motion 2021, as well as last year’s female champion, eight invited athletes, one local Greek wildcard and two spots for the winners of the Red Bull Art of Motion Online Qualifier.” When I asked Nico about the backlash to the gender imbalance, he said it was mostly a miscommunication — it should’ve said four women instead of three on the main page. I’m not sure this would’ve made a big difference to the community. It’s two fewer than the previous year and far from equal. A lot of community members believed that Red Bull missed an opportunity to include more women with invitational slots, not to mention the other two women’s podium winners from 2021. Still, Nico underlined that it was a learning experience, with plans to continue listening to the community and step up their communications strategy for future events.

And we have seen meaningful community dialogue create change, even if it takes time. Take SPL — for years they received public backlash for not offering equal prize money and for years they didn’t budge on that particular issue. SPL did continue to evolve in other ways to support the women’s community, adding a separate women’s division for Speed early on in 2013 and later for Style and Skill in 2015 and 2017, respectively. But when I spoke with Tom in May 2022, he noted they still weren’t ready to offer equal prize money, emphasizing concerns about low participation numbers among women and overall event costs. Someday, he said, but not yet.

Despite those reservations, SPL kept talking with community members, and a few key conversations did eventually change their minds. When I asked why the change of heart, Tom explained, “After consultation with female athletes and hearing out the broader parkour community, we’ve elected to provide equal prize money. We are leaders in sport parkour and we want to continue to lead by example. Despite not having any additional funds, we are taking a risk. Ultimately, we believe that equal prize money is the right thing to do. We want to ensure the actions we take as an organization will foster larger female participation in parkour.”

By the Numbers

How Participation Levels Affect Decision-Making: Art of Motion and Sport Parkour League

When discussing the question of equal pay for women in parkour competitions, several event organizers raised the issue of participation numbers. Overall, there are still fewer women than men doing parkour, which is, of course, evident in the competition scene as well. Nico estimated that women’s participation in both the online and onsite qualifiers for Red Bull AOM was around 12–20 percent over the years, while Tom gave a similar figure of about 13 percent for SPL qualifying events. That number was higher in SPL’s last major competition in 2019, with women representing nearly 40 percent of the total participants. SPL likely has one of the highest participation percentages because they take the approach of offering the same number of competitor spots to men and women — even if they don’t always get filled. However, the lower number of overall women competing was SPL’s primary reason for not offering equal prize money for a long time. So, we have AOM on one side offering equal prize money but fewer spots to women, and SPL on the other side offering an equal number of spots but unequal prize money. Both occurring for the same reason: fewer women competing.

Having a smaller number of women competing makes it difficult to rationalize an entirely separate division. This is where the community faces a chicken and egg debate: should event organizers wait for more women to compete before creating more opportunities, or should they create the opportunities to increase the numbers? Most of the organizers I spoke with saw the logic in both approaches, agreeing that if you create the space, people will fill it. On the other hand, many of them also felt it was a significant risk for their business, doubling their costs to add another division without knowing if it would pay off. Still, I think more and more event organizers are coming to the same thought that Air Wipp Chairman Emil Breman underlined, “You don’t get rich making these decisions, but you need to think about the community.” And the money will come as we continue to grow as a sport.

Switching It Up: A Look at New Competition Formats

Tempest Freerunning and Air Wipp

Tempest Freerunning’s TMPST Onlines, which began in 2020, was one of the first competitions where I noticed a significant number of women participating. After an initial successful run, Tempest added a separate women’s division with equal prize money and ran the competition monthly throughout 2020 and 2021, switching to quarterly in 2022. The first time they included a women’s division, nearly 80 women submitted for 32 initial bracket slots — an extremely high number for a parkour competition and not too far behind the men for that round either. Create the space and women will fill it. However, submissions have decreased since that first round and the numbers have often dipped too low to consistently hold a 32-person bracket for the women’s division. As a result, Tempest has shifted to a 16-person starting bracket when necessary, but remains committed to providing equal prize money.

The lucky winners of the previous TMPST Onlines would eventually be invited to participate in Tempest’s KOTC event in April 2022. Unfortunately, with a few repeat winners, some dropouts, and other issues, Tempest didn’t quite have an even number of men and women for KOTC. When men drop out, there’s always someone to take their place. When women drop out, there’s fewer women at the highest levels who can jump in at the last minute. So, Tempest carried on with two brackets: 16 men and 8 women. Tempest CEO Gabe Nunez explained that because of the participation numbers, the men would actually be competing one more round than the women, making the question of equal prize money a bit more complicated. In the end, they opted to divide the money by round, with each round being worth $2,500. This meant that Tempest was able to offer $10,000 for the men’s winner and $7,500 for the women’s winner.

Another important aspect of the competition was how the rounds were presented. While KOTC was a closed-door event and the footage hasn’t yet been released, Gabe shared that the way they filmed it was intentionally inclusive, prioritizing the men’s and women’s rounds together rather than creating two separate events that could be aired separately too. This is an important distinction that can make a big difference for how the athletes experience the event themselves and how the audience perceives the athletes. In 2018, when Air Wipp first offered equal prize money for separate men’s and women’s divisions, they also moved the women’s final onto the same day as the men’s final at the request of one of the athletes. By shifting the schedule, the women had a chance to compete in front of a full stadium and livestream audience rather than other athletes there for the qualifiers and random passersby. It seems obvious in retrospect, but someone did have to ask for that change to be made. This is why it is critical for women and other underrepresented groups to have a voice in decision-making.

Pr/etty Parkour and the Asian Parkour Championships

In many of these cases, change has come from individual conversations with decision-makers or direct requests by athletes for adjustments to be made. But we’ve also seen people going out and doing it themselves. An excellent example of this is Pr/etty Parkour’s online Pretty Flow Competition. Feeling intimidated by most of the current competition formats as beginners, Pr/etty Parkour co-founders Prim and Hetty (get it? Pr/etty?) came up with the idea of a flow-centric online competition, seeing flow as the ultimate equalizer. Men tend to dominate in strength and power-focused formats, but despite being considered “girly” and therefore lesser in the past, “flow actually takes a huge amount of skill and creativity, as shown by all our competitors both female and male,” Hetty explained.

Another online competition to prioritize flow and creativity in 2021 was the Asian Parkour Championships, which, in addition to offering equal prize money for the men’s and women’s divisions in the individual Rail Flow category, also required mixed gender teams in the Team Flow category. Making inclusion a requirement like this can help break down barriers, but it can also risk tokenizing women, which only serves to maintain that feeling of marginalization. Still, these all serve as useful examples of how switching up event formats, judging criteria, and team structures could help to address gender inequality in parkour competitions.

Judging and Other Professional Opportunities

In addition to equal prize money, separate divisions, and marketing decisions, inclusivity also happens at the judge’s table and on the business side of things. We’re a small sport, to be fair, and even smaller at the highest levels, but there are a good number of qualified women to judge parkour competitions and they’re not always called upon. In one case this year, it took a man turning the job down and recommending his female colleague for the gig to see a woman on the judging panel. This isn’t always the case. There have been many competitions — including this year — that included women on the judging panel, but it’s still not the norm. Inclusion needs to happen at every level of competitions for us to really make progress — from the athletes competing to the judges making the calls, from the marketing materials used to promote the event to the people designing the courses, we need different perspectives across the board.

Likewise, athlete sponsorships and pro team spots, especially paid pro team spots, remain limited within the parkour community in general and for women in particular. That being said, they do exist and they have been increasing in recent years. In addition to blazing her own trail as a competitive athlete, Luci Romberg led the way in this area too when she became the first woman to join the Tempest pro team back in 2008. Luci also went on to have ownership in Tempest businesses, which is a rare and inspiring step for women in the parkour community. Since then, at least a dozen other women have become sponsored athletes or joined parkour teams, a few of whom have secured sponsorship deals, joined parkour events as special guests and invited athletes, served on judging panels, and much more. There have also been a small number of women-led parkour clothing lines and other business ventures over the years.

We should definitely celebrate and continue to be inspired by these trailblazers. And, we should continue pushing the envelope until we no longer have any “firsts,” until we can no longer list all of the professional female freerunners at once because it would take too long, until it is the norm for women to have equal access to opportunities and success in this sport.

Zooming Out: A Look at Other Sports

We often talk about these issues in a vacuum as if parkour is the only sport to face them, but of course that’s not the case. We are one of many action sports within a broader society grappling with issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Looking at the issue of equal pay, some sports achieved parity decades ago, such as the Equestrian World Cup Dressage Final in 1952, while others only recently equalized the purse, such as the World Surf League in 2019 and the Cliff Diving World Series in 2020. It seems to be trending upward in recent years, with a 2021 BBC study finding that 34 of 37 surveyed sports that offer prize money had reached parity for at least one major championship. That means more than 90 percent offered equal prize money in 2021 compared to about 70 percent in 2014 when the BBC first ran the survey. Keeping in mind that’s for at least one major event, not all events, but it does demonstrate significant improvement in the last decade.

Unfortunately, the fight is far from over. Women continue to face barriers to entry and pay inequality in many traditional sports such as basketball and soccer (football). The Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) stands as a stark example of pay inequality in U.S. sports. On average, WNBA players make 44 times less than their male counterparts in the NBA, according to international media. And let’s not forget the battle that the women comprising the U.S. Women’s Soccer team have been fighting for six years, pushing for the United States Soccer Federation (U.S. Soccer) to grant them equal pay and equal treatment. A settlement was finally reached in February 2022 stipulating that U.S. Soccer would pay out $24 million to former and current players and commit to equalizing pay between the men’s and women’s national teams in all future competitions. The efforts of the U.S. Women’s Soccer team inspired countless other teams around the world, with Norway signing an equal pay agreement in late 2017 and the Dutch football association agreeing to equalize pay between men and women by 2023.

Likewise, it’s taken years of robust advocacy efforts to effect change in the action sports industry and there’s still a long way to go. In 2019, the World Surf League announced it would provide equal prize money to men and women, which is a monumental step in the right direction but it still only applies to League-managed events. Other companies continue to lag behind, such as O’Neill — a surf brand that hosts a competition called the O’Neill Freak Show in Santa Cruz, California, which remained an all-male event until last year. It should’ve been a moment to celebrate when O’Neill finally added a women’s division in 2021, but the new addition came with far fewer competitor slots — eight women compared to 64 men — and significantly lower prize money — $1,000 for the women’s winner compared to $10,000 for the men’s winner. Following significant public backlash, O’Neill eventually changed course and awarded equal prize money to men and women at the event in December 2021, but it raised a lot of concern within the surf community that even after the World Surf League decision and the Equal Pay for Equal Play Act in 2019 (we’ll get into that below), a company still initially proceeded with plans for an unequal event.

One of the most common arguments that decision-makers employ to rationalize offering fewer opportunities for women is that women just aren’t as interesting to watch. But research shows that’s not actually true. About 84 percent of general sports fans across the United States, United Kingdom, France, Italy, Germany, Spain, Australia, and New Zealand were interested in women’s sports, according to a 2018 Nielsen sport study. And what’s even more telling is the breakdown within that 84 percent was 51 percent male and 49 percent female. So, women and men are interested in women’s sports. Moreover, general sports fans found women’s sports or athletes more inspiring and more progressive than men’s, while men’s sports or athletes were perceived as more money-driven than women’s, according to the study.

Lastly, another area where we often see inequality play out in other sports is in the uniform requirements and expectations imposed on women but not men. Across different sports, women’s outfits are policed and criticized. Women are told to wear less and wear more. From gymnastics, to handball, to tennis, women have been subject to intense scrutiny and outdated rules, keeping us stuck in a misogynistic past and distracting from the game itself. On a positive note for the parkour community, that seems to be one problem we have managed to avoid in parkour competitions. Men and women are equally free to wear whatever they are comfortable competing in, with no strict requirements either way. Let’s make sure we keep it that way!

Equal Pay for Equal Play — What Does the Law Say?

So far, any discussion of equal prize money in parkour has mostly been a cultural conversation about parkour values and hard business decisions. But are there any laws that apply?

I won’t attempt to cover laws in every country, but we can dig into two key laws here in the United States: Title IX (Federal–1972) and Equal Pay for Equal Play (California–2019).

Most people in the U.S. have at least heard of Title IX before, especially with its 50th anniversary being celebrated this year. What some people may not know is that it was pivotal in increasing — and allowing at all — women’s participation in sports. Title IX states that, “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any educational program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.” What that means is that any program or activity receiving federal funds must provide equal access and opportunity to everyone.

With this law, the United States has seen women’s sport participation numbers skyrocket. Since 1972, the number of women participating in sports has increased by more than 1000% at the high school level and by more than 600% at the college level, according to the Women’s Sports Foundation (WSF). Women’s participation also increased at the highest levels of competitive sports. In 2016, we saw the largest cohort of female Olympic athletes in U.S. history, with women comprising nearly 53 percent of the U.S. team compared to just 20 percent of the 1972 U.S. team. The figures mirrored the stats around the world that year, with women comprising about 45 percent of the athletes competing at the 2016 Olympics compared to only 26 percent in 1988. Needless to say, investing in women and girls pays off.

However, it must be noted that not everyone has enjoyed the same increase in access to sport since Title IX was enacted. Women of color, transgender and non-binary athletes, and people with disabilities continue to face significant barriers to entry and full participation. In its May 2022 report, 50 Years of Title IX: We’re Not Done Yet, WSF underscored that, “Providing safe spaces for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) athletes and sport leaders remains an urgent consideration.” The organization also emphasized that, “Female athletes with disabilities continue to receive fewer opportunities to pursue their athletic dreams,” while “Asian, Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and other girls and women of color participate in sport at lower levels, face greater barriers to participation, and are historically excluded in sport leadership.” It is critical that parkour business and community leaders understand these barriers and take a proactive, intersectional approach to women’s inclusion. We must ensure equal access and opportunities for all women athletes and sport leaders, including women and girls of color, differently abled individuals, and LGBTQ+ athletes.

The other critical piece of legislation that applies to these conversations in the U.S. is the Equal Pay for Equal Play bill — or Assembly Bill 467 — that passed in California in September 2019. The law outlines that sports events held on state land must offer the same prize money to men and women competing in the events. How does this play out in real life? Well, it meant that when the Mavericks Challenge organizers went to apply for a permit from the California Coastal Commission to hold the infamous big-wave surf competition in northern California, they were required to offer equal prize money for the women’s division in order to receive the permits and proceed with the event.

It’s a huge step forward, as was Title IX, despite the limitations of these laws. Title IX only applies to programs and activities receiving federal funds, and Equal Pay for Equal Play only applies to events held on state-owned lands. However, each law demonstrates a strong commitment from lawmakers and points to an ongoing cultural shift that values women in spaces that were created for and traditionally only available to men.

The Way Forward

There is still much progress to be made, and the parkour community has a real chance to do things differently as a relatively young sport. We have an opportunity to invest in women and girls far earlier in our sport’s history than other sports have done. We have an opening to stand up and declare not just that women are welcome to tag along, but that women — all women — are actively encouraged and supported to succeed in this sport we all love so much.

How do we do that? By speaking up and taking action. I’ve included 10 recommendations below for parkour community members and competition organizers to carry into their work.

10 Actions to Support Women’s Inclusion in Parkour Competitions

For Competition Organizers

- Make an official statement that your parkour organization or company supports equal prize money in parkour competitions.

- Follow through on #1. Offer equal prize money at any competitions you host or partner with. And before I lose you with the simplicity of the first two steps, read #3 and #4!

- If you are unable to or choose not to, be fully transparent about why you are not offering equal prize money or an equal number of spots.

- Clearly communicate and advertise how athletes can participate in your qualifying events and overall competition to help reduce barriers to entry.

- Determine and publicize minimum participation numbers for each competition category prior to an event (for example, each category must have at least 3 athletes to proceed). This will prevent any confusion when too few participants sign up for a category and event organizers decide to cancel it as a result. Minimum participation requirements should exist for all categories — men, women, youth, masters, etc. — not just the categories that event organizers expect to be smaller.

- Hire women, including differently abled, LGBTQ+ and women of color. Look around at your organizing team, your judges, your course designers, your financial decision-makers. What does your team look like? If everyone looks the same, it might be time to diversify your team. Moreover, ensure the women on your team are valued and respected. And please don’t bring women in just for women’s initiatives. Women can coach, judge, and otherwise be involved in men’s events just as men can coach, judge, and support women’s events.

- Invest in women and girls. Many communities have increased the overall number of women and girls in co-ed classes and events by holding separate women-only classes and informal meet-ups, which create a safe and approachable entry point to get started. This can feed into the competition space too. Host speed courses, competition-focused workshops, and friendly competitions for women and girls.

For Athletes and Community Members

- Make a collective statement outlining the reasons why you don’t support an organization’s decision and the changes they can make to regain your support. We all love a good Instagram naming-and-shaming when we’re feeling heated, but to see real change, a joint statement with athletes’ signatures would be more powerful and put organizations in a better position to respond in a less defensive way.

- Get out there and create change. Don’t like how things are being done? Start something new and do it better.

- Create a Women’s Parkour Alliance to represent women’s voices and advocate on behalf of women in parkour competitions. See other sports for examples, such as the Women’s Skateboarding Alliance or Surf Equity.

Bonus Recommendation for All

- Lastly, talk to each other. It sounds basic, but there’s so much progress that can be made from community discussions. Is the community upset by a decision you or your organization made? Host a discussion or create a feedback loop so they can be heard. Don’t like how an organization is approaching an event? Send them a message. We’re still such a small community when it comes down to it, we should be taking advantage of that and working together to create positive change.